INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ORTHODOX THEOLOGY

2/2 2011

Mémoire des deux mondes. De la Révolution à l’Église captive

Paris. Cerf, 2010 (Collection «L’histoire à vif»). 528 pp.

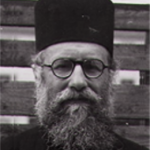

This remarkable book tells us the fascinating story of Basil Krivochéine (1900-1985), the son of a minister in the Tsar’s government, who joined the Army of the Volunteers of the «Whites» during the Bolshevik Revolution, became a monk in the Russian Monastery of St. Panteleimon on Mount Athos, a priest of the Russian Orthodox Parish of Oxford and Archbishop of Belgium of the Patriarchate of Moscow.

During his life, he spent 19 years in Russia, 22 years on Mount Athos, and about 40 years of exile in the Russian emigration. At first glance, the book appears eclectic: it consists of two parts (the Revolution and Church memoirs), five chapters in total that do not seem to have anything in common except the figure of the author. It is true that they were all first published separately during the life of the author, and were only put together after his death. But this is only a first impression. In fact, a careful reader could easily make a link between the first part and the second part, where «this explains that», showing the unity of the entire book as well as the author’s integrity.

The second chapter on «the year 1919» is immediately followed by the three chapters of memoirs of the author as archbishop. One can be surprised, as was Metropolitan Nikodim Rotov (p. 344), why nothing is being said about his decisive period of life on Mount Athos. We know that the young monk Basil was expulsed from the Holy Mountain in 1947, being suspected by the Greek authorities of pro-soviet sympathies. But nevertheless, the first part of the memoirs helps the reader to understand Krivochéine’s attitude in the second part.

The first part describes the adventures of the young 19 year old boy fleeing St. Petersburg, his native city, in order to join the White Army during the cold winter in 1918-1919. To do that, he infiltrated the Red Army, by pretending having a very important mission to carry out.

Thus, the son of Minister Krivochéine, who confesses having had in his youth sympathies for the spirit of the Revolution and some expectations for a «new Russia» (p. 26, 42), soon considered the soviet system as unbearable and odious (p. 47). Nevertheless, he never severed ties with his fatherland. During his whole life, he always stressed that he was Russian, although not a Soviet citizen. In fact, he remained stateless until 1978, when he only took Belgian citizenship. All this perhaps explains why he has chosen to remain as a clergyman within the Patriarchate of Moscow, with the aim of helping and defending the captive Church, while other fellows had either joined the Patriarchate of Constantinople or constituted the «Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia».

Thus, the Revolution and the civil war described in the two first chapters explain Krivochéine’s affinities and repulsions towards different representatives of the «Captive Church» in the second part of the book. The whole chapter 3 is dedicated to Metropolitan Nicolas Iarouchevich who had approached Basil Krivochéine at different occasions and through different ways, even through the Soviet Embassy, was curious to hear Krivochéine’s report on the situation of the Russian monks on Mount Athos. The exiled Athonite monk had then suggested to the leading figure of the Russian Orthodox Church of that time to send about ten monks to St. Panteleimon, otherwise this monastery would cease to remain Russian (p. 235).

Chapter 4 deals with Metropolitan Nikodim Rotov presented as «an unpleasant and repellent personality» (p. 290) who «does not serve the Church but the State» (p. 326-327) but whom the author appreciates for his resistance against «the pretensions of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of an almost papal primacy and attempts to monopolise the preparation and convocation of the future Council» (p. 306). This major figure of the Orthodox Church in the Soviet Union is responsible for the renewal of Russian monasticism on Mount Athos in the 1960’s (p. 358-359). Perhaps this achievement is the reason of Krivochéine’s «absolution» of Rotov’s two major «capital sins»: his pro-sovietism, which made of him a «theologian of the October’s Revolution» (p. 350-353), and his pro-catholicism, which led him to receive Roman Catholics for communion in the Orthodox Church (p. 355).

Chapter 5 tells us the story of the local Church council election of Patriarch Pimen in 1971. Here, we see how the Soviet system managed to overcome Krivochéine’s attempt of contesting the procedure of that election with only one candidate and an open vote, which was perceived in the West as a Soviet provocation, and his strong opposition towards the ecclesiastical charter of 1961, inspired by Soviet laws. First, Metropolitan Nikodim Rotov tells him that «there will not be only one candidate» in order to calm him down (p. 407). Later, Krovocheine is brought to the conclusion that there are no suitable candidates other than Pimen (p. 425). Finally, Krivochéine’s Exarch asks him to stop his war against the new ecclesiastical charter, which Krivochéine considered as anti-canonical. His Exarch, Metropolitan Anthony Bloom, told him: «I think that if we, the bishops abroad, are the only ones to protest against the decrees of 1961 while all the others keep silent, this will be interpreted as if we want to appear as heroes and as if the local bishops would be cowardly and traitors of the Church. Through our intervention, we would accuse our brothers who are in a much more difficult situation than ours, and we would act up as heroes». (p. 482).

This book is an inescapable source for the history of the Orthodox Church under the Soviet regime. Besides recalling the story of a young noble joining the White Army and who later became bishop in the Russian emigration, and his relations with the Patriarchate of Moscow, it enables the reader to become more acquainted with major ecclesiastical figures of that period such as Filaret Denysenko, Filaret Vakhromeev and Alexis Ridiger, in addition to those previously mentioned. Also of value are the footnotes, which could serve as a prosopological dictionary. However, it is disappointing that the editor had not included an index, which would have facilitated its usage for research.

The book gives us also an inside view of the Church under Soviet captivity, within which took place not only the practices of lying and of «negationism» (such as the negation of Khrouchev’s persecutions by Nicodim Rotov on p. 311), but also the policy of silence and blackmail, even imposed on such outsiders like Krivochéine. «I do not advise you to talk, you may not be able to leave from the Soviet Union», the archbishop of Riga, Leonid, told him once (p. 435). Krivochéine finally chose silence. Nevertheless, he died in his native city, Leningrad at that time, during his next (and final) visit to the USSR.

Archimandrite Dr. Job Getcha is Professor of Dogmatic and Liturgical Theology at the Institute of Graduate Studies in Orthodox Theology in Cham-besy-Geneva, Swiss