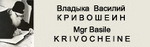

Archbishop Basil of Brussels, head of the Russian patriarchal diocese in Belgium, died at the age of eighty-five in the night of 21-22 September 1985, during a visit to Russia. He was familiar figure at summer conferences of the Fellowship in Abingdon and Broadstairs during the 1950s, as many older members will recall. By the wider world he will be remembered above all for his work on the eleventh-century Byzantine mystical writer, St Symeon the New Theologian.

Archbishop Basil (in the world, Vsevolod Aleksandrovich Krivoshein) was born at St Petersburg on 30 June 1900, the son of the distinguished Russian statesman Aleksandr Krivoshein. His father, a close associate of Stolypin, was Minister of Agriculture in prerevolutionay Russia during 1908-15, and in the civil war acted for a brief period in 1920 as head of the civilian government in the Crimea under the White leader General Wrangel. Vsevolod, the future archbishop, was a student in the philological faculty at Petrograd University when the Revolution began in February 1917. He transferred for a time to Moscow University, but soon left for the south and joined the White Army. Evacuated with other anti-Bolshevik troops to Egypt, he made his way in 1920 to Paris, together with the other surviving members of his family. Here he resumed his university studies at the Sorbonne, receiving the degree of licencié ès lettres in 1921.

In 1925 Vsevolod Krivoshein enrolled as a student at the newly-founded Theological Institute of St Sergius in Paris. But in November that same year, drawn to the monastic life, he went to Mount Athos, and entered the Russian Monastery of St Panteleimon, which at that time still numbered more than 500 monks. On 24 March 1926 he was made a novice, and on 5 March 1927 was clothed as a rasophore — the first of the three monastic grades — receiving the new name of Basil (Vasilii). He spent altogether twenty-two years on the Holy Mountain, becoming thoroughly proficient in the Greek language, and for many years acting as the monastery’s secretary for Greek correspondence. In 1937 he was elected a member of the monastic council at St Panteleimon’s, and during 1942-5 he represented his monastery in Karyes at the sessions of the Holy Community, the central administrative body on Mount Athos.

It was during his years on the Holy M ountain that Fr Basil laid the foundations for his exceptional knowledge of the Fathers. The first fruits of his patristic reading are to be found in his essay ‘The Ascetic and Theological Teaching of Gregory Palamas’, which was originally published in Russian in Semimrium Kondakovianum VIII (Prague 1936), subsequently appearing in German translation in Das ôstliche Christentum, and in English translation in The Eastern Churches Quarterly III, 1-4 (1938) (reissued separately, with revisions, in 1955). Concise yet full of detail, the work is based on the relatively limited range of Palam as’ writings at that time available in printed form; but it is highly perceptive in its judgements, and still retains its value today. It anticipates by two years the monograph on Palamas by the Romanian theologian Fr Dumitru Staniloae (Sibiu 1938), and so Fr Basil may justly be honoured as the pioneer of the contemporary Palamite renaissance.1

With his knowledge of foreign languages, Fr Basil was called upon to function as representative of his monastery and of the Athonite community during the second world war, when Northern Greece was occupied by the Germans and the Bulgarians. Some of his actions during this troubled period, in themselves justified and undertaken in good faith, were later misinterpreted as ‘collaboration’. He also came under further attack after the war, when his hopes of church revival in Russia led him to be labelled a ‘friend of Moscow’ and even a ‘Bolshevik’. This reputation — at a time when Greece was being torn apart by civil war between the pro-Western government and the Communist guerillas — led in September 1947 to his expulsion from Athos, although he still continued to be a member of St Panteleimon’s. ‘Against my will,’ as he later put it, ‘I was obliged to leave the Holy Mountain, where I had expected to spend the rest of my life’.2 Condemned by a Greek court, he was sent to the concentration camp on Makronisos.

After his release, he settled in Athens and resumed his patristic research. Then in early 1951, through the efforts of Metropolitan Germanos of Thyateira and Great Britain, he was invited to Oxford to help with the preparation of the Patristic Greek Lexicon (eventually published in 1961-8). After receiving the written blessing of the monastery of St Panteleimon, he arrived in England on 20 February 1951, slightly less than a month after the death of M etropolitan Germanos (23 January). On 21 May 1951 he was ordained deacon at Oxford, and on the following day priest, by the Serbian bishop Irinei of Dalmatia, acting at the request of Metropolitan Nikolai of Krutitsy and Kolomna, head of the department of Foreign Affairs of the Moscow patriarchate. Hieromonk Basil was appointed assistant to Archimandrite Nicholas (Gibbes), rector of the Russian parish of the Annunciation, Oxford, and he took up residence in the church house at 4 Marston Street. While in Oxford he worked on St Symeon the New Theologian, preparing a critical text of the original Greek (hitherto unpublished) of Symeon’s Catecheses. This appeared in three volumes, with text, introduction and notes by Fr Basil and a French translation by Fr Joseph Paramelle SJ in the series Sources chrétiennes (96, 104, 113: Paris 1963-5).

Walking down the High or busy among the shelves of the Bodleian, in his monastic rason and tall hat, with full, bushy beard and long hair, Fr Basil was a striking figure. At meetings of the Oxford branch of the Fellowship, it was his custom to sit in the middle of the front row, vigilant and attentive. As soon as the speaker had ended — sometimes, indeed, before he had done so — Fr Basil was ready with the opening comment. His questions, although courteous, were frequently devastating in their directness. His English, at first idiosyncratic, quickly grew in fluency. With my inner ear I can still hear him saying, with his high-pitched voice and characteristic sing-song intonation, ‘Again and again in peace. . or ‘to the ages of ages’. In the Litany for the departed, when he came to the phrase ‘a place of light, a place of verdure, a place of refreshment’, he used to say firmly ‘a place of refreshments’. When I was undergraduate I found him kindly yet somewhat remote; for in Oxford, as later in Brussels, he continued to be always an Athonite monk.

On 14 June 1959, at the Russian cathedral in Ennismore Gardens, London, Fr Basil was consecrated titular bishop of Volokolamsk and auxiliary in the Russian patriarchal exarchate of Western Europe. Then on 31 May 1960 he was nominated bishop of Brussels and Belgium, being raised to the rank of archbishop on 21 July of the same year. He remained at Brussels for the rest of his life, in charge of the small patriarchal flock in Belgium, and continuing always with his study of Symeon.

Fifty years of patristic inquiry were crowned by the appearance of his major work Dans la lumière du Christ: Saint Syme’on le Nouveau Théologien 949-1022. Vie — Spiritualité— Doctrine (Chevetogne 1980, pp.426). It is a work of deceptive simplicity. Deliberately, through an act of academic kenosis, Archbishop Basil refrained from providing an elaborate bibliography and a mass of learned footnotes, although he could very easily have done this. He had as his purpose something harder to achieve: not to engage in dialogue with other specialists over points of detail, but to provide for a wider readership what he termed ‘a portrait of this great saint that is living, objective, fully documented from the words of Symeon himself, and above all truthful’ (p.7). In this he succeeded to a remarkable degree. It is true that here, as in his other writings, he is a faithful witness to tradition rather than a creative thinker. But his book is one that could have been written only after many years of intense study, spent reading and rereading the sources, until Symeon’s inner world had become also his own. To use a phrase of Fr George Florovsky, he possessed a genuinely ‘patristic m ind’. With full justification Archbishop Basil could claim, ‘My book is written with deep love for Symeon’ (p.7), and here precisely lies the secret of his imaginative sympathy for the New Theologian. The book has appeared in Russian as well as French, and an English translation is awaited from St Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Archbishop Basil took part in many international congresses. He was present at each of the Oxford conferences on patristic studies from the first in 1951 up to the ninth in 1983, contributing papers at almost every one of them. From 1966 to 1984 he represented the Russian Orthodox Church in the Anglican/Orthodox Joint Doctrinal Discussions, alike at the preparatory meetings and then at the full sessions and the sub-commissions from 1973 onwards. Recalling Fellowship meetings at Oxford in the 1950s, I noted that he had not changed his debating style. Alert, quick to note inconsistency of thought or imprecision in wording, he was forthright and to the point, yet never captious or polemical. His humble sincerity, and also his sense of humour, enabled him to say things that in the mouth of others might have proved wounding, but spoken by him they caused no offence. He was staunchly Orthodox, yet a generous friend to other Christians. At the last session of the commission in Dublin in 1984, deafness at times made it hard for him to follow the discussion, but his mind was as sharp and lucid as ever.

Archbishop Basil was always faithful to the Moscow patriarchate, but this did not prevent him from protesting firmly against interference in church life by the Soviet authorities. At the episcopal assembly preceding the Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church in May-June 1971, his voice was one of the few raised in favour of a secret ballot at the forthcoming election of the patriarch (the eventual vote was in fact open). On the same occasion he attacked the uncanonical parish statutes of 1961, which impaired the proper authority of the priest within his parish. In 1974 he expressed clear support for Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn at the time of his expulsion from Russia (as was also done by Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh). Following the 1976 Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Nairobi, he sent an open letter to the general secretary of the WCC, Dr Philip Potter, thanking those who had spoken out in defence of Russian Christians under persecution. ‘I wish to affirm my heartfelt gratitude’, he wrote, ‘to all those who at Nairobi raised their voices in defence of religious freedom in the Soviet Union, so putting an end to the scandalous silence that has prevailed until now on this subject. I hope that the struggle for the rights of believers in Russia will continue.’

Archbishop Basil’s long life, embracing the three different worlds of prerevolutionary Russia, Mount Athos, and Western Europe, ended in the place where it had begun. In September 1985 he travelled to Russia, and on the 15th celebrated the divine Liturgy at the cathedral of the Transfiguration in Leningrad, the church

in which he had been baptised eighty-five years previously. He felt unwell after the service and was taken at once to hospital. Here, a week later, he died. In accordance with his own expressed wish he was buried on Russian soil, at the St Seraphim cemetery of his native city.

+ KALLISTOS OF DIOKLEIA

1. Twenty-five years earlier a work on Palamas appeared in Greek by Grigorios Papamikhail

(Alexandria 1911), but this had relatively little impact, even within Greece itself.

2. Address at his episcopal election, in Messager de l ’Exarchat du Patriarche Russe en Europe

Occidentale 32 (1959), p.213.